That title might be a spoiler.

Due to the lapses in the preservation of PC gaming history, I don't think it's popularly understood nowadays how much of a big deal Phantasmagoria, Roberta Williams' tale of a couple who buys a Maine mansion built by a famed illusionist and gains a husband-possessing demon in the bargain, was in its day on several fronts. It was ragingly popular, for one - an epic production spanning seven CDs, from the premiere designer of the premiere studio of what at the time was a mainstay genre, marking their first foray into FMV technology and a more adult story than what King's Quest offered. For another, its inclusion of an in-game hint system sparked a big debate about the game's difficulty, its perceived championing of FMV's glitz and wow factor over challenging gameplay, and its potential "dumbing down" of the adventure genre. This may sound utterly inconceivable, particularly if you've played Phantasmagoria, but the fate of the protagonist's husband Don was, at the time, the third leg of tragic gaming deaths right up with Nei and Aerith, with the AOL board consumed with gamers unaccustomed to not being able to save everyone as the main character and have everything turn out OK, desperate to find a way to avert the doomed character's fate. (The panic was also fed by it being the dawn of the internet, the first time that large numbers of gamers could communicate across the country en masse to try to solve a gaming problem. I still remember the sea of topics on attempts and disproven theories and questioning as to whether this was possible, pierced by one amiably fed-up guy, who had achieved enlightenment through acceptance, posting: "Let Don die!".)

I finally dove into Phantasmagoria after discovering an LP of the sequel, Phantasmagoria: A Puzzle of Flesh, by its lead actor, Paul Morgan Stetler. (Stetler is also doing an oral history of the game, which was panned in its day but has assumed new significance by its showcasing of queer issues in a time when relatively on-the-level treatments of such material were scarce.) Though I didn't have a computer capable of running it, Roberta Williams and horror were in my wheelhouse - I kept abreast of the controversies, the efforts to revive Don, but I had never played through the damn thing.

OK, now: It's fashionable to turn precious and declare anything without the complete gamut of modern comforts - frequent autosaves and 4K 60 FPS and a chyron reminding you of your current objective - "unplayable." I don't want to say Phantasmagoria is in the modern day "unplayable" - but, at least for a lengthy adjustment period, it comes real close. Blowing up the resolution of the FMV on a 3840 x 2160 screen renders a heck of a lot in motion just an indistinct blob, even with the "Movie Detail" option on. The decision to make the environments entirely virtual - while understandable, considering Sierra's budget presumably didn't include funding for the construction of a nightmare castle - creates this weird playhouse look that has aged horribly. It was assuredly far more impressive in the early days of 3D graphics, and it looks better in screenshots than it does juxtaposed with FMV characters in motion - some of these stills are quite lovely in a fantasy way - but during gameplay, it looks cartoonishly fake when the atmosphere is going for horror and digitized realism. In the early going, it's almost impossible in some cases to figure out what exactly the things you're carrying are from their little primitive 3D renders. (To inspect your items, you're supposed to tote them over to the icon on the right, which is, allegedly, a closed eye; I had read the manual before playing, but this feature proved so unintuitive that it completely failed to spark my memory of the instructions.) A number of interactions with the environment will just yield the equivalent of different idle animations that massively waste your time. The pacing of human interactions during cutscenes is dead in the water. And the music: it's atrocious, perhaps the worst I've encountered in a major commercial release - atonal MIDI plinking, with a rhythmic chant that's comedic instead of oppressive and gives a clownish backdrop to horrific scenes. Playing through this, it's amazing that the Playstation Clock Tower and the first Resident Evil were less than a year away - and that Kenji Eno's D, which is leaps and bounds above Phantasmagoria in terms of presentation and its understanding of cinematic techniques, had already been released.

One of the elements that has aged the most poorly, however, has to be the story's attitude toward spousal abuse. This is ironic, since the game is by one of the medium's founding female developers and is explicitly about a very female fear: the man you married turning into an abusive creep. Despite this overt theme, the game has a tin ear for how it frames Don's behavior post-possession. He's insulting his wife Adrienne; he's shouting and screaming at her; he's ordering her not to leave the house; he's throwing things at her and grabbing her and not letting go and yanking her around; and she acts like, oh, you're just being so weird! Even when Don kills the family cat (spoiler: the cat dies), Adrienne reacts with only a passing burst of frustration ("that son of a bitch!"), as if he got drunk at a party or something. Also, though the acting is for various reasons uneven, Don's actor is doing almost too good a job with his body language in portraying a physically-strong person who's perpetually attempting to intimidate a weaker individual, letting them know he's just holding back but is willing to drop that reserve at the slightest excuse. By far the biggest source of tension for me in the game, beyond any of the haunted-house gore, was holding my breath during Adrienne-Don interactions, expecting him to haul off and wail on her and the game to no-sell it. It's utterly bizarre how Phantasmagoria can identify and present so many real-life abuse behaviors and yet not expect the player to be anything but mildly confused in response.

(An added part of the problem here, I think, is that the game falls down in establishing Adrienne and Don as a loving couple for pre-possession contrast. The closest they come is the tenderness of the opening sex scene; afterward, in the first chapter, they come across as awkward strangers. Adrienne's puzzlement and patience might be a bit - a bit - more understandable if it were demonstrated that the relationship had a solid foundation beforehand...though, even then, I'd be wondering why Adrienne hadn't considered a potential medical issue behind her husband's severe change in temperament following his possession-adjacent concussion.)

It is here that I must utter words that are never welcome in one of these essays: it's time to talk about the rape scene. (Warning for this entire paragraph.) I'm actually surprised, given the limited cognizance of sexual assault in the '90s, that this was identified as rape - unless, unfortunately, Sierra and Williams labeled the scene as such as part of look-how-mature-we-are marketing. (At no point does Adrienne say "no" or offer resistance, though it would be outright dangerous by this point for her to do, and Don's turn in behavior here happens suddenly; it does not pass the enthusiastically-given test, and Don is blatantly unconcerned with her reaction or consent.) Williams has talked about how she believed the scene was necessary to illustrate that Don had turned, but if you don't think something is wrong with Don by this point from his other behavior, I don't know what to tell you. Furthermore, the staging of the scene - the facial expressions and spastic physical actions - invites derision in a context where absolutely no comedy, no matter how unintentional, should be. It seems as if the creators wanted to be horrifying and sensationalistic but also not extremely explicit or put their actors through more of a trial than necessary, and pulling off such a balance of venal ambitions and noble reservations with a subject as delicate as sexual assault would have been difficult even if this team weren't so inexperienced in the language of film. As it stands, the scene is at once too much and inept at what it's trying to be, and the devs bit off way more than they could chew.

The acting is hit-and-miss overall, in fact, though (as is typical with these '90s FMV extravaganzas) in ways that aren't entirely the actors' fault. Adrienne is a nothing character throughout, saddled with a clueless demeanor in the face of perpetual spousal aggression, with much of her screen time consisting of the empty, protracted staring, sighing, and shoulder-shrugging that results from most of the environmental interactions that the devs thought fascinating solely because a digitized human being was on your computer screen. (This brings to mind Calvin & Hobbes cartoonist Bill Watterson's observation of how, since Calvin's parents were often stuck in disciplinarian mode by their son's antics, he had to expand their characterizations through what they were doing whenever Calvin barged in; if the devs had given Adrienne some flavor and unique observations in her reactions, they would have been more than dead air, and her character would have benefited.) I found the actress vastly improved when given an actual live human being against whom to act - most notably, the crucial conversation with the Old Man Who Knows All the Secrets - and I have to wonder how much Sierra's decision to go full-digital in environments hurt the actors here. If Ian McKellen found it difficult to act under Peter Jackson against nothing but blue screens, then Phantasmagoria's cast must have found its task exponentially more difficult.

(Also, the lack of editing undermines everyone here, with characters pausing, fidgeting, or looking down at their feet during conversations or actions for what seems like an eternity. Video games are extremely unforgiving of dead space, with the player itching to get back into control. Trim. Edit. That's something I have to learn with wording translated scripts: that things have to be kept more sprightly than in real life.)

Don's character is the one most upset by the game's misguided story choices, which do not serve or support the good points of his effective performance as an abusive husband; at least the actor opts to have some campy fun in the chase scene. It's way too late by that point to turn Don into a fun character, but get whatever you can out of the role, I guess. The actor playing the mad magician Carnovasch fares the best here, as he's experienced enough to direct himself and is not actively undermined by other storytelling choices. The script unwisely introduces a mother-and-adult-son pair of vagrants squatting on the property for comic relief: the mom's actress, while not unskilled, is doing a broad type of stage humor that doesn't really suit the story and might not jive with the audience for computer games, while the son has a mental disability that's depicted in a fake, clownish, and typical-'90s insensitive manner. (That said, the mother is the only character who's adequately disturbed by Don's behavior, flatly telling Adrienne that he's dangerous and that she needs to get out. )

One way in which Phantasmagoria was indeed ahead of its time was in its relative brevity and player-friendliness, despite it engendering a fair bit of controversy back in the day. Slicing the story up into seven days provides convenient stopping points for play sessions - and I appreciated the progress bar on the save screen, which informs you of how much of the current chapter you have left before its conclusion. Williams stated in an interview for the hint book that she wanted to approach audiences that found it difficult to finish conventional computer games for various reasons, and Phantasmagoria comes off as very conscious of accommodating adults with schedules who can't devote their entire day to entertainment. (I, for one, was grateful that the game was considerate enough to tell a complete story without eating up 60 hours of my time.)

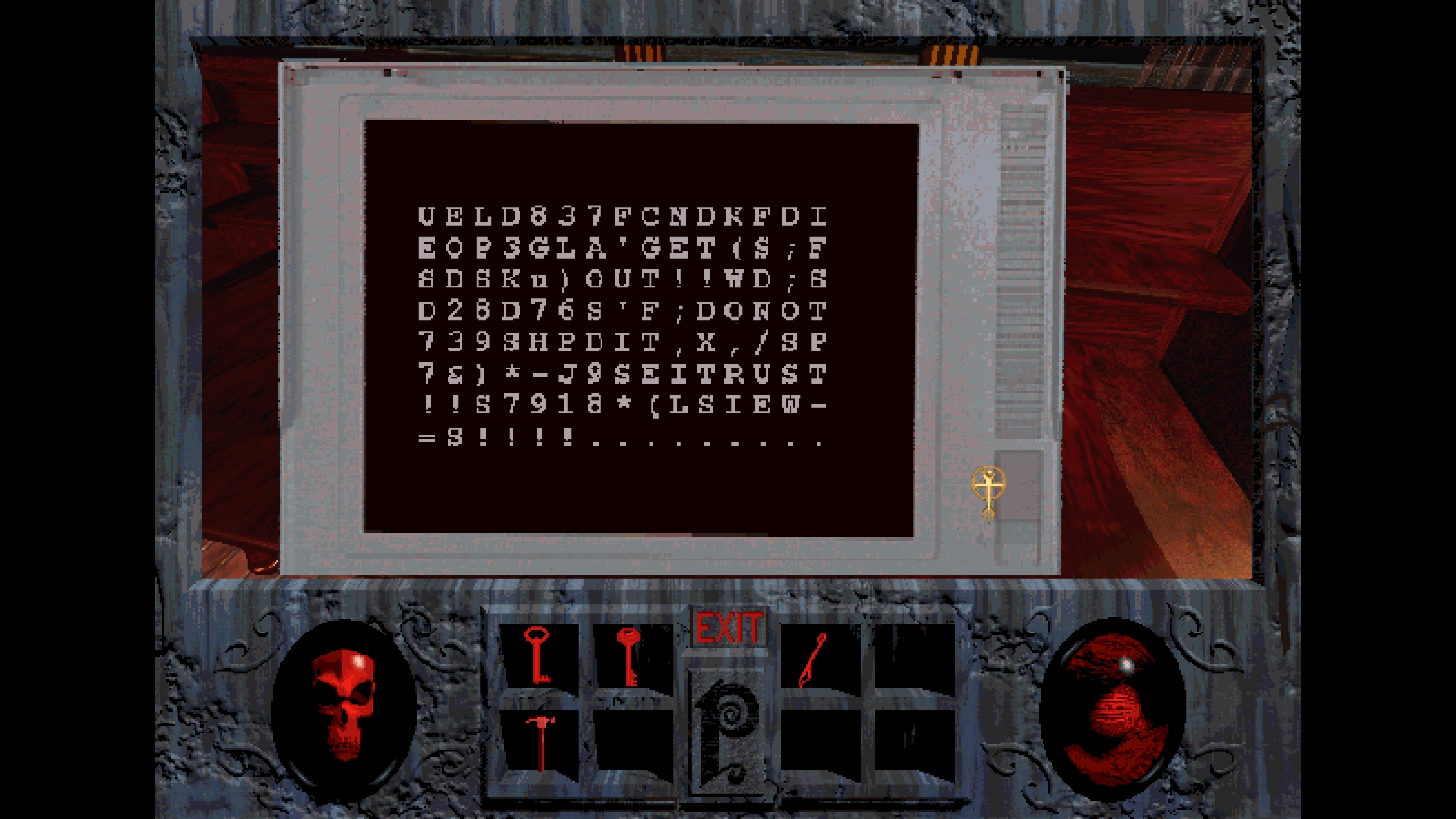

The game also offers an option to restart on any given day, even ones you haven't reached in your save file, with the inventory you'll need at that point - of which I did have to avail myself, as even in our modern cloud-based era, my save managed to corrupt itself on day seven. I'm a lot more sympathetic to concerns about sacrificing gameplay and thoughtfulness for glamour than many would be these days, when high difficulty is considered by some to be offensive, but I actually do like the built-in hint system - it's convenient yet not a tell-all, simply directing you to the room where you'll find your next objective. Where Phantasmagoria missteps puzzlewise, in fact, is when it attempts to create artificial difficulty through cheapness: a photo hidden in complete darkness in a corner of the frame; a ridiculous bit, that led me to waste an hour in pointless exploration, where the game prevents you from exploring a dark space without a light - you might think you need to find a lantern or candle to pair with those seemingly-otherwise-unusable matches in your inventory, but it turns out you just need to use those matches on yourself (which isn't how anything else works in the game). These are rare, though, and while I would have appreciated some more earnest attempts at tougher puzzles, I didn't need them. In a way, Phantasmagoria plays like a predecessor of today's walking simulators, and I don't mean that as an insult: it understood before most of us that exploring a virtual environment and advancing a story solely through exploration can create a viable, satisfying virtual experience.

The last major topic that merits discussion, I think, is the game's vaunted violence. The game is explicitly going for a story about misogyny and violence against women, and it has all the pieces in place: an abusive husband; a serial wife murderer; the killing of a child, where the authorities dismiss the wife's accusations and side with the powerful abuser; the sexual assault scene; Don's thesis exclamation, before at last outright trying to murder his wife, that "a woman's body is a wonderful thing, but the head is useless!". (All of Carnovasch's Bluebeard's gallery of wives, as well as potentially Adrienne herself, are killed, notably, via mutilation of or through the head.) Again, though: the game's refusal to acknowledge the most consistent and pressing source of anti-female violence, Don's behavior, undermines this message, while the horror and violence - and suffering - inflicted on Carno's wives are showcased as spectacle. (The grotesque FMV deaths are one of the few elements of the game that largely retain their power; I excused myself during the force-feeding death, as life is finite.) Phantasmagoria profits in a horror context from the torment of its women without committing to the message it's allegedly trying to sell and ends up celebrating the very thing against which it's supposed to be railing. This contradiction is not without precedent in horror - see: Dario Argento - but it is still A Problem.

Elsewhere, the game's horror tastes tend toward the gross-out: demonic hands ripping heads apart like monkey bread; the transient son butchering a rabbit like roadkill, complete with squelchy sounds; animated, talking ectoplasmic vomit. A lot of fun stuff has came out of Mortal Kombat, but in the '90s, it cemented the idea in the video game medium that "mature" equated to gross and gory, and despite its higher aspirations, Phantasmagoria owes more to the realm of Fatalities than it might be willing to admit.

One very bizarre choice, by the way, comes with the introduction of a completely new mode of gameplay in the last chapter: a protracted Clock Tower chase where you run around the mansion with Don in hot pursuit and can use various inventory items and objects in the environment to fend him off or evade capture. This chase is completely optional. If you have collected all the items you need for the finale by the time you enter the darkroom - and why wouldn't you do a full sweep of the house before entering, as Don's previously-inaccessible lair is clearly a point of no return - you will automatically be transported to the finale. (Well, there is one item that is unlikely to be collected your first go: a spellbook you need that's located in the darkroom itself and blends palettewise into the decor, which is likely to evade your vision, as you're preoccupied with fending Don off with a different item in the environment at the time. You can pick the book up immediately after attacking Don, but if you don't collect it then, you'll have to lead Don on a bit of a loop and then return to the darkroom.) It's completely bizarre, but somehow keeping with the game's general level of awareness, that it stumbled across something entirely new for the Western video game scene, something that would elsewhere by itself fuel an entire subgenre of horror game, but didn't think it notable enough to make it mandatory.

As for the big question of "Is it worth playing today?": No, not as a gaming experience in itself. There's a lot that jars when approached with modern sensibilities, but above all, the story isn't worth it. It's not all-the-way unpleasant, but there's enough unpleasant about it to leave a bad taste. It is, however, historically significant and weird in a somewhat-intriguing way. At the dawn of CD technology, I cut out of following gaming trends for a while due to a variety of reasons, but, removed from the zeitgeist and ATTITUDE of the day, it's a fascinating era in retrospect. There's a newness not only in what was being produced but in the mistakes made - not only by gaming devs who had no idea how to use the new freedoms of the CD format or stage cinematic scenes, but also by new entrants to video gaming from the worlds of literature and film, trying to tell stories on this new-to-them medium but struggling with its conventions. For the latter, see Overblood, which has trouble animating simple walk cycles. Phantasmagoria, despite its strengths and ambition, is quite often a prime example of the former - a sign that even the industry's brightest lights would be challenged by these new horizons, and that new strengths and skills would be required to leverage them. It's a snapshot of what many thought was going to be the future in a very awkward growing-pains time in gaming - and it's significant that its biggest selling points, its use of FMV and sensational material, have aged the worst, while its truly controversial decisions, regarding its user-friendliness and awareness of limitations on adults' free time, have proven to be the most forward-looking and prophetic.

How did they sell this house, by the way, with half the rooms locked and unviewed by the new owners, or at least Adrienne? You bought a home - or let your husband buy a home - without seeing the basement & foundation? That might be symbolic of committing to a relationship without fully knowing one's partner in another story, but it's established that Don's violence is caused by possession, not latent psychopathy.

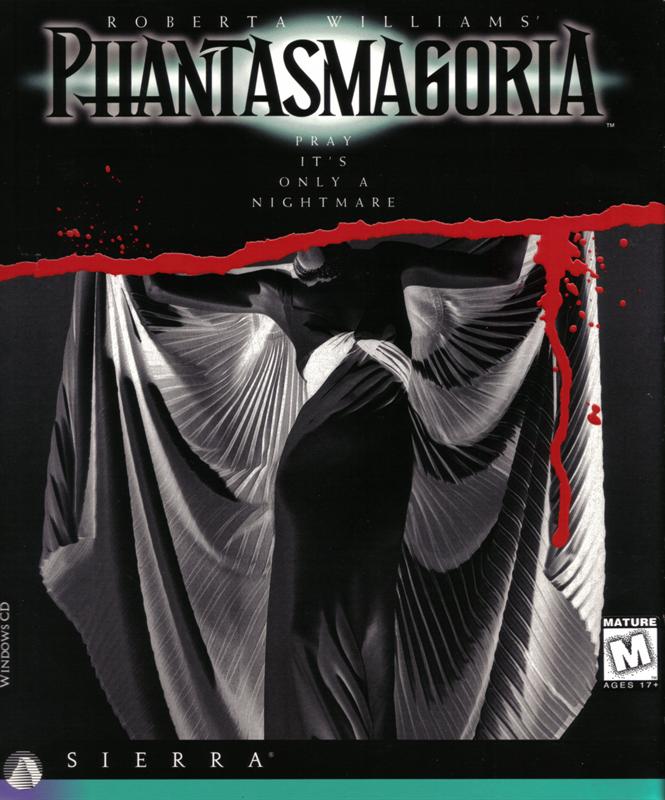

At least we'll always have that box art.

I leave you with the words of the companion book Sierra produced for the game - part hint book (more explicit than the in-game system), part behind-the-scenes production diary, part backstory depository in the Japanese tradition - on what gamers in the day might have been thinking at the close: