You may take that ironically or unironically. I live in Maine, after all. Here, the true terror begins when the snow flies.

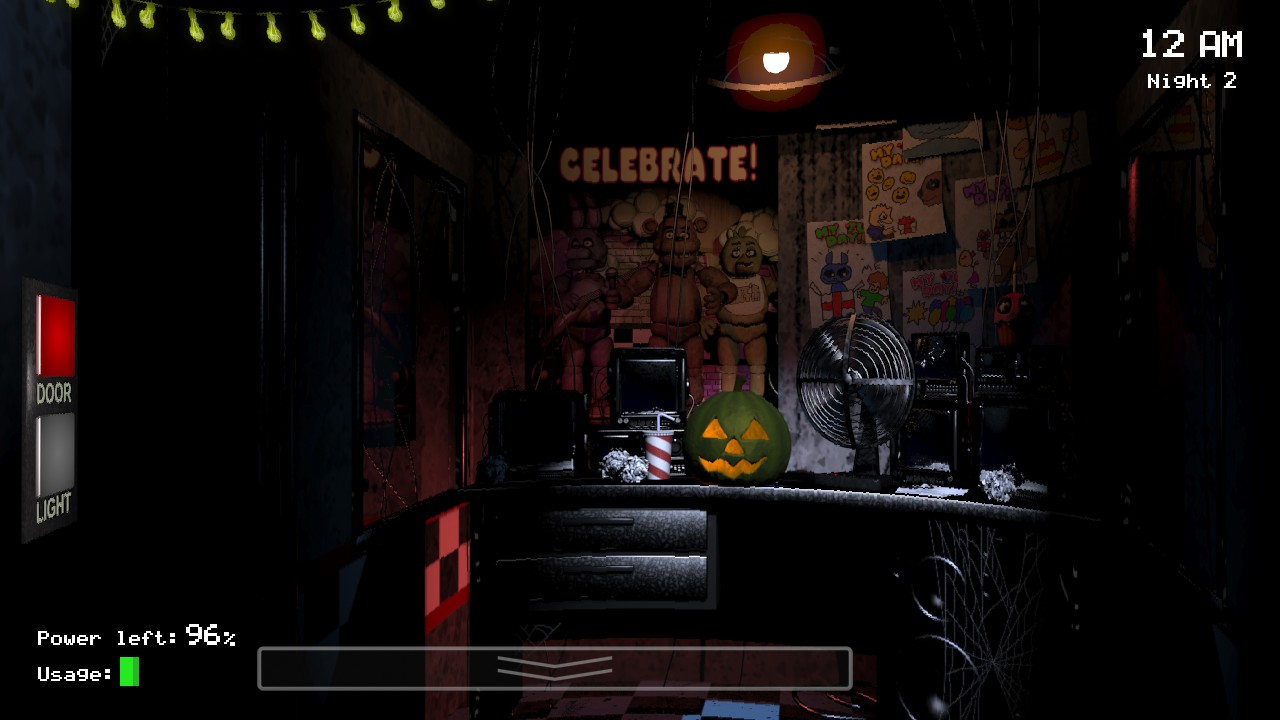

Five Nights at Freddy's

I've finished 3 and 6 in this series after a fashion (3 by getting the incomplete bad ending, 6 by building a perfectly safe and fun pizzeria that operated utterly without incident!), but I've never actually played the original despite owning it for years. 2014 is hardly an ancient vintage, but at modern resolutions, the technical seams show a bit. There's not quite as much life imparted to the main tableau through motion and lighting as we would expect nowadays, and the font is notably jaggy. The ubiquity of the thing has also ruined most of its surprises: I imagine stuff like the trick to Foxy and the wrench it throws into your normal rounds would've been really satisfying to figure out in the day, but given how thoroughly popular knowledge has dissected FNaF, the game loop is quickly reduced to mindless chores (check Foxy's and Freddy's cameras, then the two doors; repeat ad nauseum). That said: I did not know that Freddy operated in a manner similar to Foxy; I thought he appeared only when you exhausted your power. I wish I could say I figured out how to deal with him on my own, but no; I checked an FAQ to ascertain his mechanics, as the game was wearing thin for me`at that point (Day 4) with its other secrets divulged.

I'm sounding negative here, but it's important to note that while my play experience was compromised by popular knowledge, the game gets so much stuff right about horror that's so often botched: the simple controls, which avoid distraction from onscreen events and facilitate and encourage reactions borne of primal fear; the utter lack of direction or signaling of scares; the use in a still, deserted after-hours environment of the slightest of stimuli - the sounds of shuffling feet on the carpet; staticky interruptions in video feed - to foster dread. Scott Cauthon knew how to work his limitations to his advantage. Also: while the series eventually drowned itself in depressing lore, I think one of video games' greatest jokes is the first title's complete, and wholly conscious, lack of explanation for the malevolence of those animatronics. Of course they roam the pizzeria hallways at night in search of blood. Look at them. Who wouldn't think that?

D

Hey, it's time to self-plagiarize from a Steam review again:

D was everywhere in its day, the dawn of the 3D era, and many of the reviewers at Steam (where I originally posted this review) are zeroed in on its historical import. I think two aspects are of particular note regarding its success. One, though the 3D graphics are limited (but quite good for the time), the game really illustrates how far knowledge of the language of film - editing, timing, shot composition - can go in making even a primitive 3D environment effective. D feels leaps and bounds over its contemporaries even though it's not really that much more advanced technologically. Two, though visionary director Kenji Eno's prediction of "digital actors" appearing in different roles from game to game didn't come true, his focus on his main character and her range of expression adds life where none exists in lesser titles. Eno gives the proceedings time to breathe, allows for reactions of astonishment and befuddlement and frustration and reflection from the heroine, and events seem more natural, relatable, and human for it. They go a long way in helping to tell a story largely without words.

The game does still work, I think, provided you give some latitude for the two-hour time limit and don't mind investing in a scouting-out playthrough if you're coming in cold. There's genuine tension and atmosphere, and the end of the bug flashbacks is a heck of a reveal.

If you prefer the view from the backseat, supergreatfriend's LP, which provided my first experience with the game, provides an excellent tour. (He also revisits it in a later stream with additional commentary - and pro strats!) One of my most potent memories of SGF's main runthrough came from a poster on the thread who related how he came together with his college roommates to play the game, the group entranced as they traded theories as they got a little closer to the truth each evening. They seem to have been exceptionally slow at unraveling its mysteries, but it is a testament to the game's ability, particularly in its day, to cast a spell.

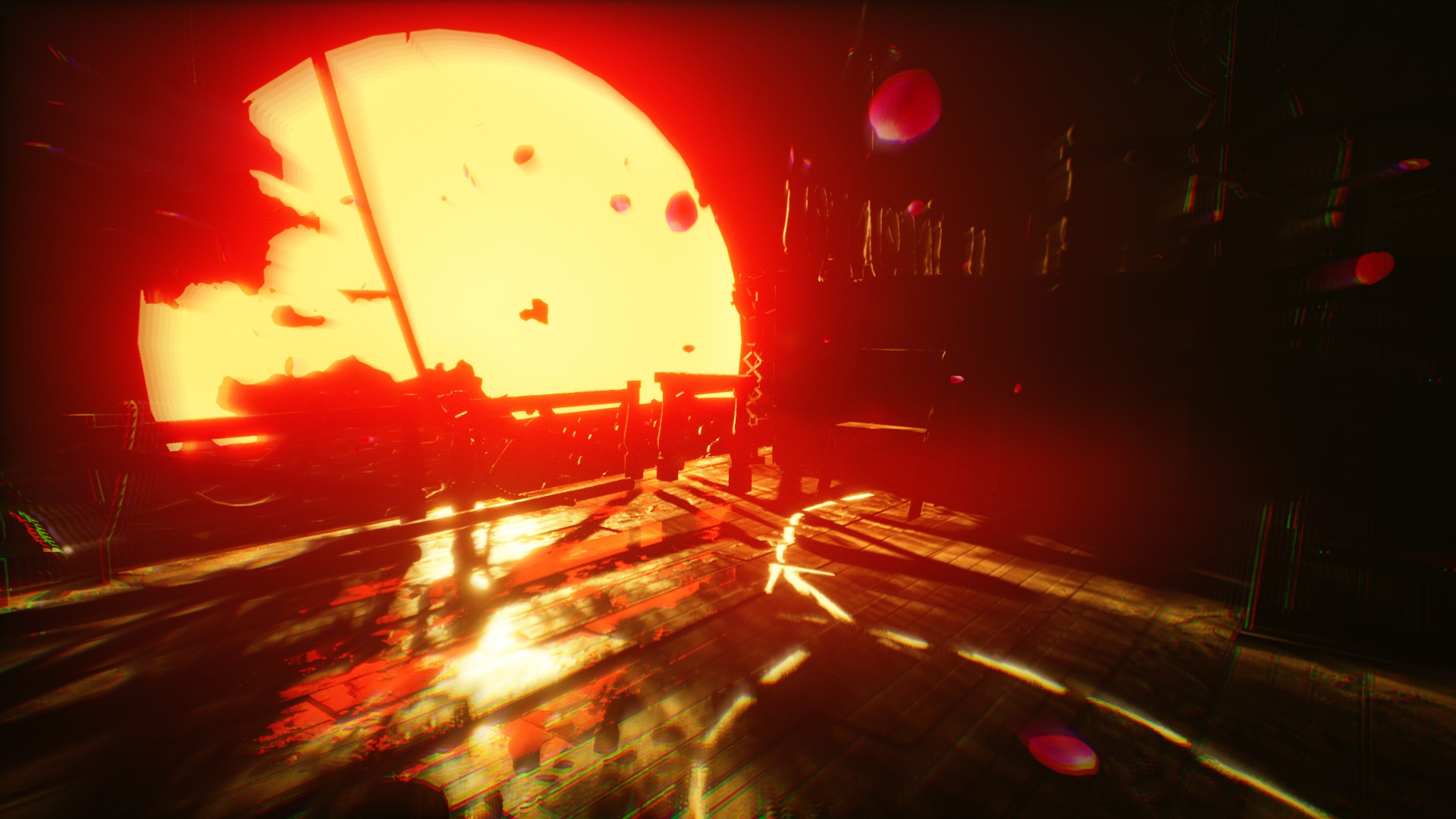

Layers of Fear 2

This entire review is going to sound like I'm out of my mind, but you're going to have to trust me. You know the thing when you're in a tight space and you're trying to open a door that opens toward you, and you kind of have to squeeze yourself around the door, moving it inward as you finagle yourself around its edge, to get by? This game - this nominal horror game - is centered around replicating that experience. I'm not kidding. They made doors extremely finicky and awkward to open and get around in their engine, and then they based gameplay around negotiating them. This sounds like utter lunacy, and yet I'm not wrong, because the puzzles explicitly hinge (ha, ha) on the door parts being difficult to negotiate. They don't make sense otherwise. Like, there are several sequences where you're chased by mannequin enemies, and the only way to put enough distance between you and them is to close doors behind you, and if opening & closing doors were a straightforward process, that would be a snap, and there would be no challenge and no actual chase. But no. In fact, the vast majority of player interaction during the first half of the game consists of opening and closing an absolutely ludicrous number of doors, as if the ocean liner on which the game takes place was sponsored by Andersen.

Look: I got this game because it supposedly starred National Fucking Treasure Tony Todd, and because I found the premise intriguing - like the (unplayed-by-me) first game, it centers on the struggles of an artist, but instead of a painter, you're an actor with...actor's block, I suppose, invited aboard a cruise ship by reclusive mad director Candyman to film a life-defining role. Well, Tony Todd is barely in the dang thing; his few lines are ominous vacuities wholly unworthy of his voice; and the character's backstory consists of an extraordinarily protracted Pore Victorian Orphans routine that is really kind of ridiculous. The story is guided by four choices you make at signposted intervals, yet the game's questionable interpretation of your actions ensures your path won't reflect your character; the game outright wouldn't let make the choice I wanted at one point, and at another, it decided that I had given up and submitted to the director's instructions by, er, not doing what he wanted and going in a completely opposite direction. Then I learned that game didn't like my series of non-choices and was going to hand me a non-ending (it's one of those "moral choice" systems where your decisions have to be all one way or the other or the game throws a fit), so I made the ULTIMATE "follow my own direction" decision and opted to quit this troubled production due to creative differences.

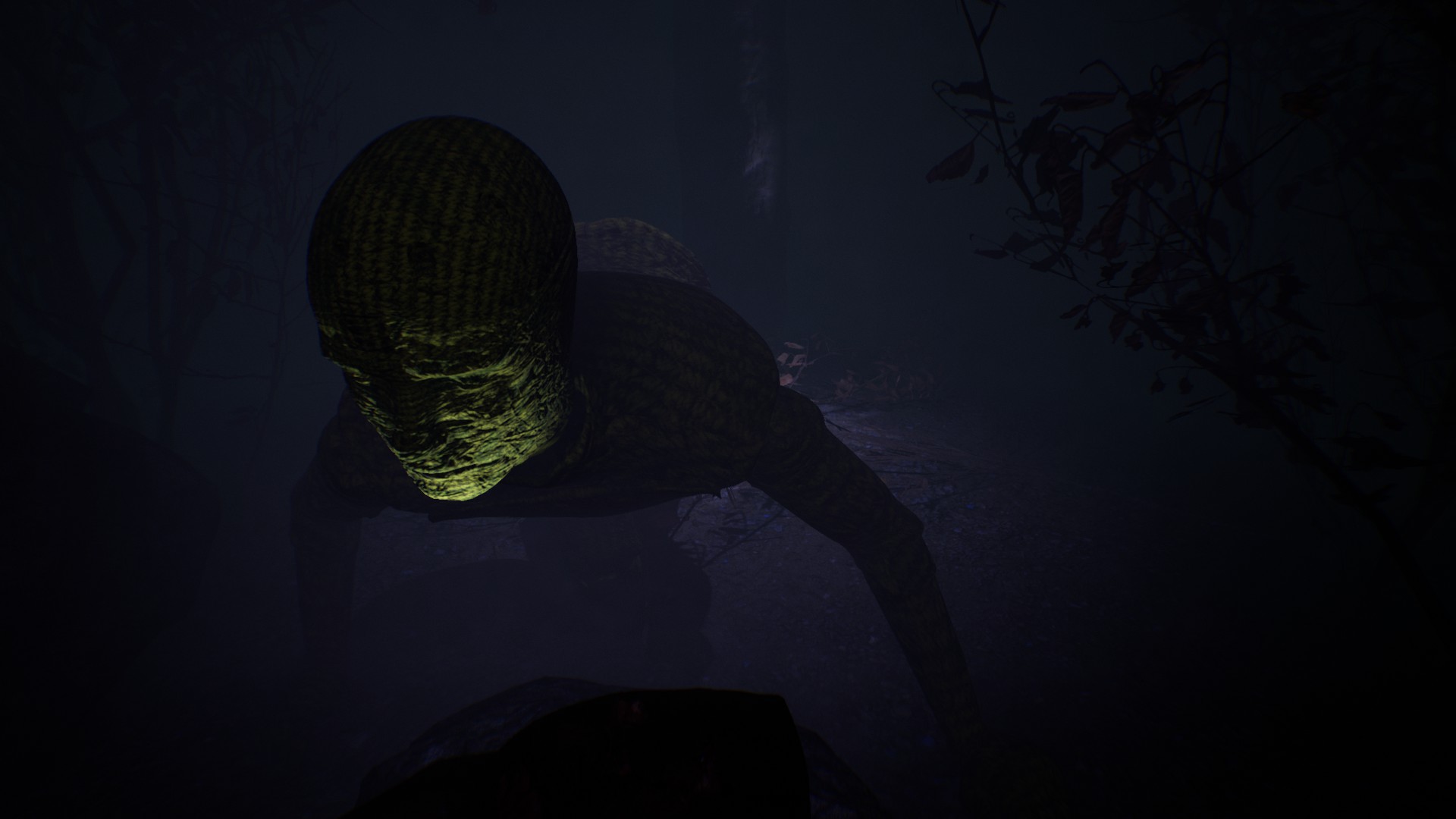

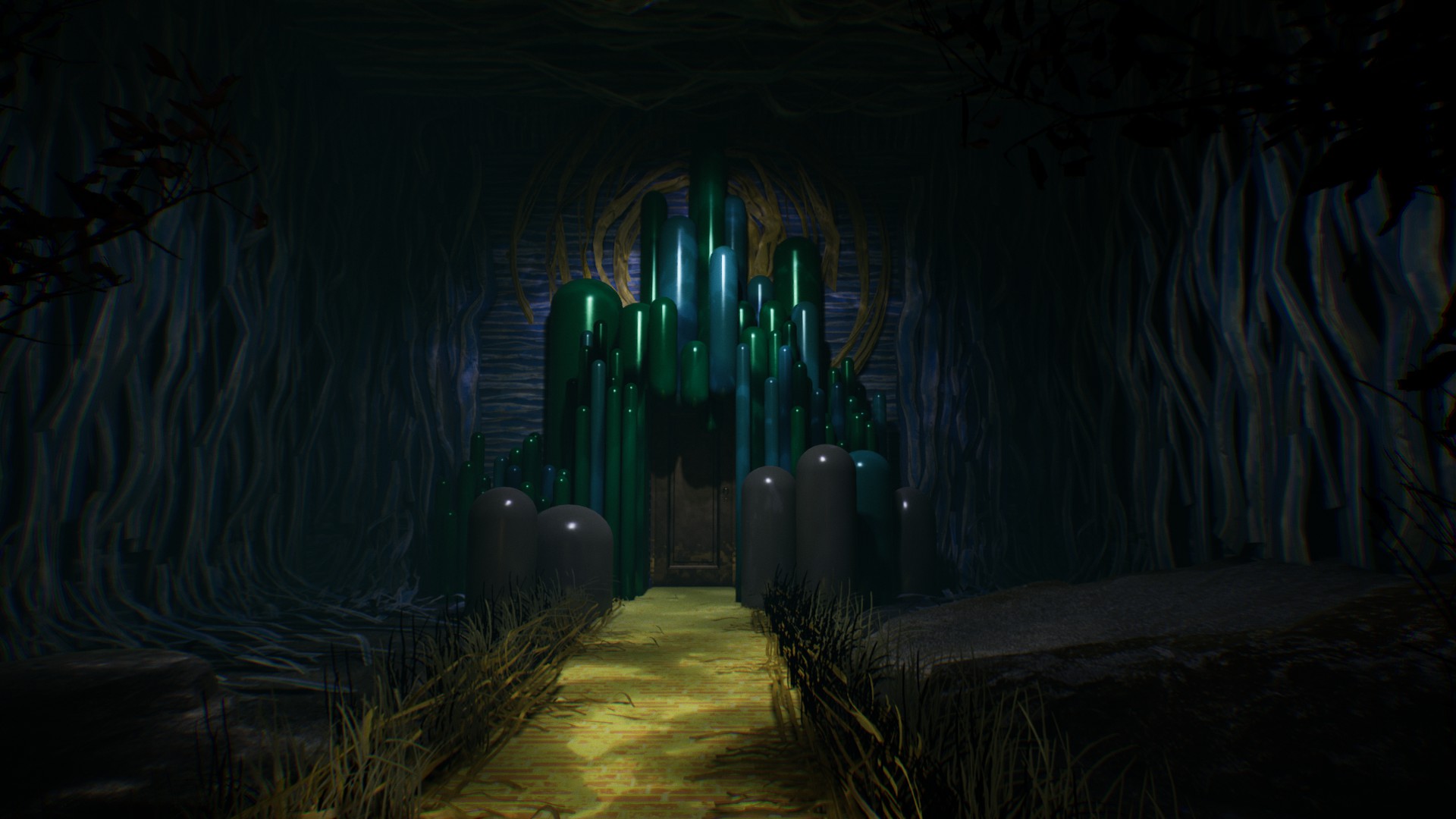

By far the worst aspect of the game, though, is the pacing. The game takes F-O-R-E-V-E-R to spell out an extraordinarily short plot; moving through the environments is like maneuvering a submarine through frozen butter; and the gameplay is almost nonexistent (again: most of the first half of the game consists of opening and closing dozens of doors). I don't think I've ever played a game this lugubrious. Making progress was like pulling teeth. This is bad news, because the devs behind this game were also handed the keys to the Silent Hill franchise, such as it is, and between this and The Medium (which I watched via supergreatfriend's playthrough), it's apparent they have no idea how to make a narrative compelling. And it's a pity, because the devs do understand certain elements of making a Silent Hill game. The underlying plot - not the stupid, interminable Victorian orphan part; the part about the underlying nature of the main character and how the truth is hinted throughout the game - is great! The symbolism of the mannequin enemies is great! There's a bit with switching between realities, each tinted by the character's feelings toward a different family member, that's great! The game looks great! I mean, look at this thing:

It would have been clever if the presentation and gameplay were at all functional! But they're not, and the game's not.

Let's end this on a Lunar reference. Maybe? The palette seems significant:

It's too Annie Lennox.