I've talked about this before, but I hated the dawn of the CD era when it was going on. Everyone was so excited about textureless Lawnmower Man polygons permanently replacing those dusty old pixels that it was enough to instill despair of art and beauty even again being a priority in gaming, and it was the start of an extended, aggressive adolescence in the medium that ended up being very hostile to women. The combination inspired me to stop following contemporary gaming until the DS era. In retrospect, though - explored in its corners, not just the marquee stuff that ended up historically-unloved and doomed the PS1 Classic to the bargain bin with its copious inclusion - it's a fascinating era because the CD medium attracted so many entrants to the video game arena, and the prospect of CD storage & sound capacity, full-motion video, and 3D graphics presented so many alien design challenges and possibilities to not only the new guys but the old hands. It's interesting to see what both those unversed in the language of gaming and those very well-versed in the old styles (as with Roberta Williams, Sierra, and Phantasmagoria) tried to do and make, and how. Sometimes, the results have priorities that are fascinatingly strange from a modern standpoint, like with the CD-i and its emphasis on a "mature" presentation over any sort of gameplay competency. Sometimes, the premises themselves seem blissfully ignorant & free of commercial considerations, like with ArtDink's caveman-evolution saga Tale of the Sun or hot-air balloon simulator NOTAM of Wind. The mistakes that are made, and the unexpected competencies, are surprising: Overblood, a sci-fi horror adventure from studio River Hill Soft, features competent voice acting and a surprisingly sophisticated score at points but struggles with simple character walk cycles.

River Hill Soft confined itself mainly to the J.B. Harold Murder Club mystery titles before Overblood, staying away from more pointy-shooty video-gamey fare, but it did have one notable trial run to Overblood in its 3DO ur-horror title and Resident Evil predecessor Doctor Hauzer. So now that we've got the metric ton of exposition out of the way: I played Doctor Hauzer. I'd had the idea kicking around vaguely for a while, but I launched into it after the estimable Kimimi reported that a blind playthrough took only about three hours - a paramount consideration for me, given that I have issues following through on any title that lasts more than an evening nowadays. In her own review, Kimimi is valiant as ever in her insistent appreciation of a game's bright spots and author intent, but I cannot overcome the fact that this goddamn thing perpetually runs like it is in pain every second it is loaded and wants to be put out of its misery with every step.

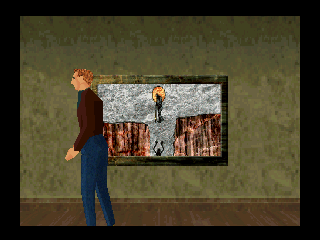

It's heck getting Hauzer to respond, but it also, as you've doubtless gathered if you've seen screenshots of the game, looks bad. That'd be more forgivable, given the era and, unlike the responsiveness issue, it not impeding basic functionality - but horror does rely on atmosphere, and outside of a room lined with creepy eye paintings, there's next to nothing giving Hauzer a sense of place, to make its environments feel lived-in; the rooms are just obstacles in a box. Appropriate, perhaps, for a mad archaeologist who's turned his mansion into a deathtrap to protect the mind-possessing artifact to which he is enthralled, but I suspect this is more a matter of lack of talent and awareness than purposeful environmental storytelling. It doesn't bear well in comparison either way: just look at what the original Alone in the Dark was doing two years earlier, imparting more character with color palettes and architectural design alone than Hauzer manages with its beige boxes.

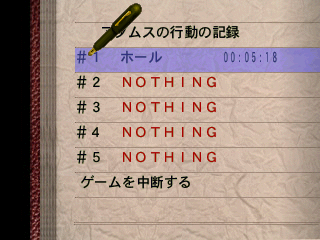

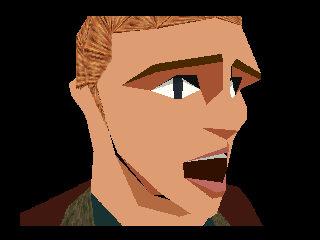

It's not like the game's devoid of ambition. The devs do make an outsized effort to create expressions with the main character's face - with polygons, not changing textures, and they spotlight the results in long, loving close-ups that wouldn't forgive missteps. Granted, those expressions consist mostly of shock (plus one admirably astute eyebrow-raised sidelong glance of wary suspicion for their reporter protag), but the emotions are, to their credit, recognizable and effective. The game does offer a unique mechanic, one I haven't seen utilized elsewhere in the genre, in its use of multiple perspectives in problem-solving, allowing you to switch between camera angles (standard third-person plus overhead and first-person views) to get a better grip on a problem.

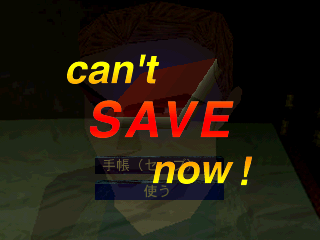

But you have to know your platform's strengths and weaknesses, and the designers here just don't know enough about video games to play to or around those, or even to identify them. They keep flinging the game with a Looney Tunes-splat into the walls of its technical limitations. There are proto-QTEs that require you to move your character quickly when the game moves at the speed of continental drift. There is, at points, significant lag in recognizing button prompts - one of those being at the "Do you want to climb this ladder to an entirely different floor?" prompts for secret passages hidden behind bookshelves in walls of identical bookshelves, where your desire to check off yet another box in mechanically, tediously Searching All the Things will launch you unintentionally into a minute-long loading screen for a destination you never wanted to visit. There are dumb and mean obstacles - an unmarked door in the opening hallway that leads to instadeath; a Raiders of the Lost Ark-style boulder trap where the rock TURNS A CORNER to follow you, exactly like in the Weird Al UHF parody - that the game has not earned enough forgiveness to indulge, the player's patience already exhausted by just getting the damn game to run. The final challenge rests on the extraordinarily shaky presumption that the "physics" "engine" is strong and stable enough to allow your character to negotiate a bullet hell segment. (At least at first glance: the bullet hell indeed is impossible, but the key to true success, be it intentionally or otherwise, proves to be just proceeding slowly.) Perhaps the very existence of the game represents ignorance of technical limitations, given how reluctant it is every step of the way simply to function.

(The damnable thing: despite Overblood's misadventures in this department, your character's walk cycle in Hauzer is fine, oddly, outside of moving four times as slowly as it should.)

I can't recommend even historical explorers muck about in this. You can usually learn something about the evolution of genres and gaming by playing early efforts like this even if the title itself doesn't quite work on its own merits, but it's so unworkable as presented that it has very little to teach. Play around with it for five minutes to get a sense of how it operates, or doesn't, then watch an LP.