Following the ActRaiser kinda-remake, Yuzo Koshiro is trying to stir up hype for a similar port of Terranigma:

Though it's been mercifully on hiatus for the past several years, I strongly dislike the "sign this petition if you want your favorite game to come out!" promotion tactic as employed by those on the production side, even if they're a global treasure like Yuzo Koshiro. Corporate decisions are not based on fan petitions; corporations are beholden to boring things like shareholders and balance sheets and keeping people employed and can undertake projects only if they make financial sense. Pretending otherwise is just manipulating fans' emotions to get free publicity for an already-upcoming release.

I have little confidence that the Square-Enix of today could handle the ending of Terranigma. I have my own reservations about it, but it's bold and profound, dealing with the biggest of issues in an unmitigated manner, and I can't see the company respecting it - being wise enough, and resistant enough to its fascination with mobile-quality bells and whistles and bloviating for its own sake, to get out of its way. Nothing approaching the concluding sequence could come out of the studio today.

That said, the ActRaiser remake was a success in that it wasn't a complete trainwreck; its reception was mixed, and outside of the lowered bars of mobile review sites, I didn't see anyone proclaiming it as a masterpiece or worthy successor to the original by any means, but it apparently wasn't a complete a mobile-asset hack job, at least. Not completely.

Which brings me to a question - initially borne out of a mistake on my part. I thought for a bit that the studio behind Mystic Ark had created Terranigma, but that was just a failure of memory on my part - Terranigma, and Soul Blazer, were from Quintet, and I had them confused with Produce, the Mystic Ark people. But: Terranigma, like the first Mystic Ark, was a 16-bit non-Dragon Quest Enix RPG that missed a U.S. release, and Square Enix seems to have learned as of late that there's money in its back catalog, even in the long-neglected Enix half of it - including the titles that never got a U.S. release. Would I want the Mystic Ark series - the SNES game and its PlayStation sequel Theatre of Illusions, from which this site takes its name - to get a release like this?

I should properly start this with "would I want The 7th Saga to get a release like this?", as Mystic Ark started as a spiritual successor to that game - but the answer there is clear: no. That title gets a lot from its austere visual and storytelling style, which really fosters the sense of a solitary journey against overwhelming odds. More banter between the Apprentices could be fun to see (there are numerous interactions that were either cut out of the original game or are rarely seen due to stacked RNG/obscure triggers), but the game overall would not benefit from friendlier, more approachable graphics or overly-chatty characters. (It also goes without saying that the U.S. version's renowned difficulty would be nerfed into the pavement.)

The first Mystic Ark also benefits significantly from silence and austerity, namely in its silent, evocative Myst-like hub world and its mysteries, as well as its sixth world, which is doing survival horror before that genre existed in full (still spoilering that; the surprise doesn't deserve to be ruined for those unaware). Its ending, where (more spoiler text) it's suggested that the main character is in fact a past incarnation of the player and that everyone has gone through their own unacknowledged struggles just to come into this world (with parental affections and significance to our existences present even in their apparent absence in our everyday lives), would also likely be ruined in a remake by dumbly well-intentioned over-explaining. As for Theatre of Illusions, I haven't gotten past the end of the second world (of presumably seven) due to an emulation issue, but as the copious production materials in the artbook make clear, in both visuals and concepts, the game was very much the baby of artist Akihiro Yamada, and that unique creative perspective would suffer in a trip to Shiny Plastic Mobiletown.

I seem very negative here, and in hashing out my feelings on this and the potential screw-ups, I suppose I am. I can't deny that I would like to see the games brought to a larger audience, though, and I would like to see what someone could do with new Mystic Ark content 20, 25 years on, even if the results are likely to be monkey's-paw in nature. I think part of this desire stems from not only the titles' obscurity but my lack of the degree of involvement I have with more beloved titles. There are parts of Mystic Ark that speak to me greatly (lonely atmospheres, understated stories, some smart storytelling moments), but the games also make significant missteps (that stupid, interminable pirate cat chapter in the first game). There's a space in my heart for it, but it wouldn't wound my soul if parts were handled incorrectly (like, say, a poorly-depicted Ghaleon would).

But then I look at this pastiche, from the Romancing Saga 3 Steam release:

The character is in standard 16-bit resolution; the barrels and trees are 32-bit; the houses and walls are 32-bit, but with some sort of smoothing filter applied; the business signs seems to be computer art that's been fed through a light pixellation filter; the illumination of the lanterns is the result of some sort of non-pixelated lighting effect; and the windows seem to be a flat CG underlay. It does have care put into it - and, significantly, many of its flaws are masked on a tiny, high-res mobile screen - but it's also wrong in a fundamental, very obvious way that demonstrates profound not getting it.

Square's most recent effort (the ActRaiser thing) is a bit more successful - but would I really want any game for which I significantly cared subjected to that treatment, even if it means new content and a wider audience? Even after mulling it over, I still can't say.

I was browsing Akari Funato's Twitter account, and I ran across a promotion of a re-release of Vheen Hikuusen on the DMM digital platform. It seems a straight export of the Birz reprint that accompanied Harmony of Silver Star's release. The art's as crisp as day and as beautiful as you'll ever see it, and the DMM reader has a much better zoom-and-enhance functionality than Amazon Japan's in-browser Kindle app - I'm seriously tempted to get it just in case I need to snip any panels. The thing is, while DMM does have its tentacles into selling all sorts of media, it's by far most renowned as a clearinghouse for every kind of Japanese porn video humanity could want. I dunno, man - I'm not an artist, and Funato's gotta do what she's gotta do, but for selling her stuff privately, God bless her, she seems to have a knack for teaming up with the most questionable companies.

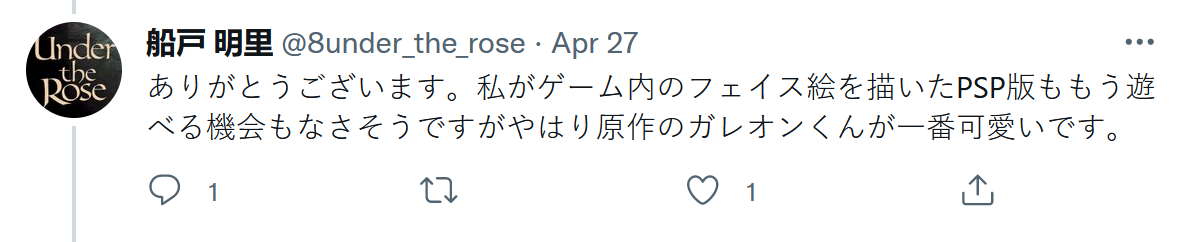

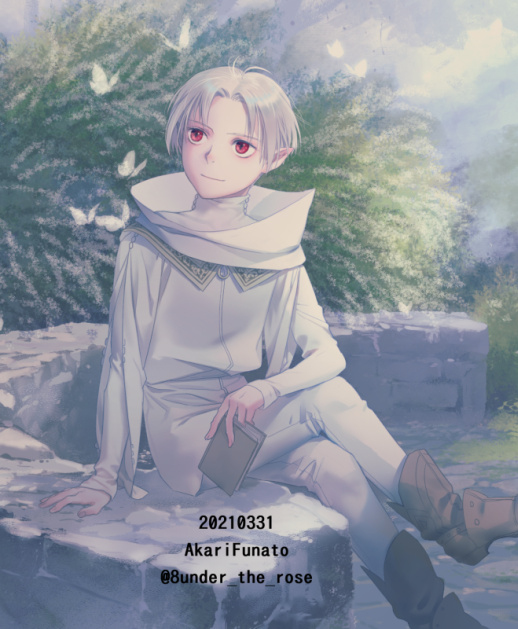

Anyhow, the real reason I'm posting: I checked out the comments to see if there were any hot author convos about my most favorite game-related thing ever - and there was a hot author convo, but not about Hikuusen specifically. Someone mentioned adoring Vheen Hikuseen but never having played Lunar, and Funato let slip that she hadn't gotten the chance to play the PSP version of Silver Star yet - even though she drew the portraits for the game:

Oh, man. I always thought that Ghaleon (in his Premier outfit) looked like a cocker spaniel in Harmony, and I took the off-model art as proof that Kubooka just couldn't do his old style well enough to draw Lunar anymore. It wasn't Kubooka. It was Funato. I can't wholly blame her, as, despite drawing key frames for Mia's intro in SSS, cel stuff was never her milieu. I tried going back to Ghaleon's PSP portraits to try to find some Funato touches I missed earlier while ignorant of her involvement, but (save for him showing a little mazoku fang in that Four Heroes portrait where he's gritting his teeth) no, no - he just looks bad.

(ETA on this a month later: I took another look at the portraits, and I see that a lot of the offness comes from Funato heavily outlining the tops and sides of Ghaleon's eyes - to make him look more evil, I suppose. The most natural Ghaleon looks is in his collapsed portrait in his final boss outfit, which completely lacks those heavy lines. As Funato's intuition usually isn't off when it comes to Ghaleon, I wonder if the lines were a studio-mandated revision to make Ghaleon appear more overtly villainous.)

At least we know how they managed to get Dyne's nose right in the game.

I also found the Skeb Ghaleon pic without the "SAMPLE" watermark, though with a different watermark, in a less-obnoxious location but now opaque, appended:

Smaller res, though, even if you do the small -> orig trick on Twitter.

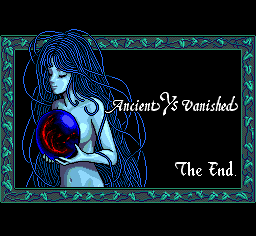

One of the other things I did in the breaks during my very busy Q4 (yes, about nine months ago) is finish up Book II of Ys. My major takeaway: It is amazing how Lunar stole absolutely everything from Ys - Alex, Luna and Lucia, Vane, Ghaleon, Zophar, pictoglyphic friezes, blue-tinged goddess real estate, entire cutscene sequences and shot compositions - and at the same time stole nothing at all, because Ys does absolutely zero with its material. Hey! These are good ideas! Why don't we tell a story with them?! Because Ys sure didn't.

I've gone over the gameplay failures after Ys I, and that assessment stands. The sequel does add a fireball spell, which makes boss fights play like My First Shooter instead of its predecessor's nonsensical non-affairs, and the puzzles are a bit smarter and more involved this time around, making varied use of a spell that transforms you into an enemy creature. Any hope for a satisfying resolution to the story set up in Ys I takes a big dive here, though, so it's the narrative missteps that have my attention. Ys II is remarkable in its ignorance of how to use the various elements of its medium - both that of the video game and the new CD-based platform on which it was published - to tell a story.

- the world's friendliest SWAT officer, who kept waving at me for stopping as he crossed the crosswalk

- obligatory yet welcome T-rexes

- very alert French bulldog (not a costume)

- Link w/ spiffy plastic shield & Master Sword

- more homemade Link with no spiffy shield but no less spirit

- twin ravens

- Among Us crewmate/impostor

- walking vampire teeth (bottom row only)

- dragon mask with homemade coat of gradated autumn leaves (supposedly the Green Man as per a later conversation, but I'm not seeing it)

- rainbow Romany girl

- homemade Cruella de Vil complete with branded Dalmatian bag

- twin parrots

- female berserker w/ fur boots

- traditional princess w/ impressive pink taffeta meringue-whip skirt

- deer bride (? woman in white dress w/ antlers)

- little girl steampunk engineer

- black & red dragon (not original, but the costume was really well-made; a well-formed fuzzy head, like a stuffed animal, with a warm cape just the right length)

- inflatable dragons; more of these than T-rexes

- Black Widow

- hot dog w/ relish ruffles on sides (overheard: "Don't pull on Mom's mustard!", even though Dad was wearing the costume; this was never explained)

- young surgeon (female STEM representation very strong this year)

- inflatable...badger? wolverine? it had sharp claws

- zombie, and that's not original, but the kid kept yelling "BRAAAAAIIIINS!!" and was impressively committed

- either an owl or No-Face from Spirited Away (this was just a mask with a short fuzzy white blanket draped from it and worn on some sort of support seated on top of the head, and while it was extremely lazy, points for originality)

- neat looking knight in faux chain mail & a red tabard plus full-face black hood/visor

- neat green fairy (Tink? absinthe personification?) with pointed wings lit w/ fairy lights

- pharaoh

- an adult wearing Pinhead's coat but not anything else Cenobite?

- someone with just a literal jack o' lantern on their head

- an older girl with elf ears, a crown, and a red cape, black vest, and white shirt; she looked good, but I got the feeling that she was someone specific and I couldn't identify her

- another homemade Cruella de Vil with a fur jacket spray-painted red on the back (maybe this happens in the new movie; I don't know)

- father in Día de los Muertos makeup & a sombrero + daughter in beautiful black & aqua Mexican-inspired princess dress

- a couple Beetlejuices, which is odd, since they were kids who should be way too young to recognize the character; they must just like his style

- inflatable BB-8 with old-school Leia (but blonde)

- a black-clad superhero whom I thought might be Black Bolt but who had some inverted-triangle symbol with vertical lines on top I didn't recognize and can't look up

- twin Scooby-Doos

- family of shiny green dragons w/ fabric wings (2 women + child)

- another female berserker (w/ skull skirt this time - to balance out all the STEM?)

- an ostrich

- little twin firemen, parents dressed as a burning building and hydrant, and a stroller doubling as a fire engine (w/ real light-up headlights)

- sentient rainbow with neat rainbow gradient light-up cape

- another deer bride, what the hell (is this a Midsommar thing?)

- guy wearing plastic molded full-head bluebird mask?

- businessman w/ head being eaten by shark

- something inexplicable: a dad dressed up as a raccoon with a daughter dressed in gray and a sandwich board saying "ROCK"? ????

- Eli Wallach from A Fistful of Dollars (this was a kid)

- glitter shark

- female lineworker

- Chica from Five Nights at Freddy's (FNaF costumes were all over a few years ago; fairly unusual now)

- tons and tons of neon light-up LED Dead by Daylight Legion-like masks with X-ed-out eyes and sewn-up mouths; it couldn't have been Legion, because they were so popular - there were literally dozens - but they looked neat

- inflatable rainbow unicorn

- a flamingo

- either just Zorro with a long, full beard or practicing Orthodox Zorro

- an older kid in a black robe holding just like a hobbyhorse unicorn head in front of him; I don't know if this was meant to communicate that he had beheaded the unicorn - the message was unclear

- evil Ralphie from A Christmas Story in his rabbit jammies w/ a bloody baseball bat

- Slipknot-loving unicorn in band T-shirt (as this unicorn passed, a kid called out: "there are so many unicorns!")

- man with just a literal tree branch tied with rope to his back

- Amanita mushroom

Page 34 of 56