ITEM: How could no one alert me to the fact that there is a new English-language Angelique fansite! Well, archive.org has it dating back to 2018 - but it's new to me, dammit, and I love it. Evidently, someone's decided to create a media gallery for the franchise (books/CDs/DVDs), along with personal notes for the books they have. It warms my heart to see someone putting in the effort to create an entirely new, big site in the English-speaking fansphere in this day and age. Or even the day and age of five years ago.

ITEM: I downloaded the Sparkle! CD of character songs for Angelique Luminarise. (Which you can do, too, through that Amazon Japan link, provided you go through the rigmarole of buying yourself an Amazon e-gift card in the exact denomination of the album price to get around credit card region restrictions - or you can stream the album on that page, if you must be so 2023.) It's actually awesome! The songs are top-class, with great variety, and they do a better job of showcasing the characters in an appealing way than all of the pre-release promo info put together. Way better than I was expecting given what had come before. Of particular note: Shuri's song, "Recollection," is not only a legitimate banger (blasting it and "Lovesick" from an open vehicle while driving down the Missouri banks near sunset is one of my fonder memories from earlier this year) but recontextualizes everything I've seen of that character and makes me really eager to learn his story.

(Also, yes: despite it being also two years after its release, I have not yet started Luminarise. It's been a strange two years, all right. Then again, this is all part of my typical Angelique game release cycle: follow everything assiduously up to the release, get the game shortly afterward, plan on doing an LP-type series of posts, fizzle out after a couple, not play the game again. I enjoy the franchise primarily through other media, it seems. If all goes as planned, I should be cracking Lunimarise open in the upcoming few weeks.)

ITEM: I've actually started pasting the lines from the Angelique translation into a spreadsheet with the corresponding Japanese text to facilitate a patch. For the Japanese text, I'm working from an incomplete online script compilation; otherwise, there would be a heck of a lot more Japanese typing than I would have to do as it is. Frustratingly, the online document is formatted in a completely different manner from the book - with text grouped by event, not character - but it's the only source of pre-digitized text I can find, and with what's looking like over 600 rows of cells per character right now, anything to cut down on busywork, however imperfectly. Even if it creates its own manner of busywork.

To engage in a bit of cynicism in an overall positive post: I frankly suspect that once I get the spreadsheet done, the goalposts will be moved yet again, and I'll be asked to do yet more of the patch work proper for none of the credit. I almost think we're never gonna see an English-language version of Angelique unless I myself learn how to put together a patch - which isn't a underestimation of the skill ROM hacking takes but a pragmatic appraisal of the extraordinary resistance this project has to movement on any front if I'm not the one directly behind it.

(Incidentally, if this beast of a project ever, ever gets done and Angelique does get patched, I'm moving to Requiem immediately and skipping Special 2. I don't anticipate a problem with introducing the new characters through Requiem, and there's no reason to delay the introduction of the series' most indelible villain or what's likely the franchise's most accessible installment any longer than necessary.)

ITEM: Recent reblogs reunited me with this Heritage Post by kathisofy, and it reminds me of how I miss fellow Angelique fans. I miss the jokes, the fan content, and the analysis of new material from the heyday of angemedia. I don't have anything deeper to say here. I hope everyone from that community's doing well, and I just want to note that I enjoyed our time together.

ITEM:

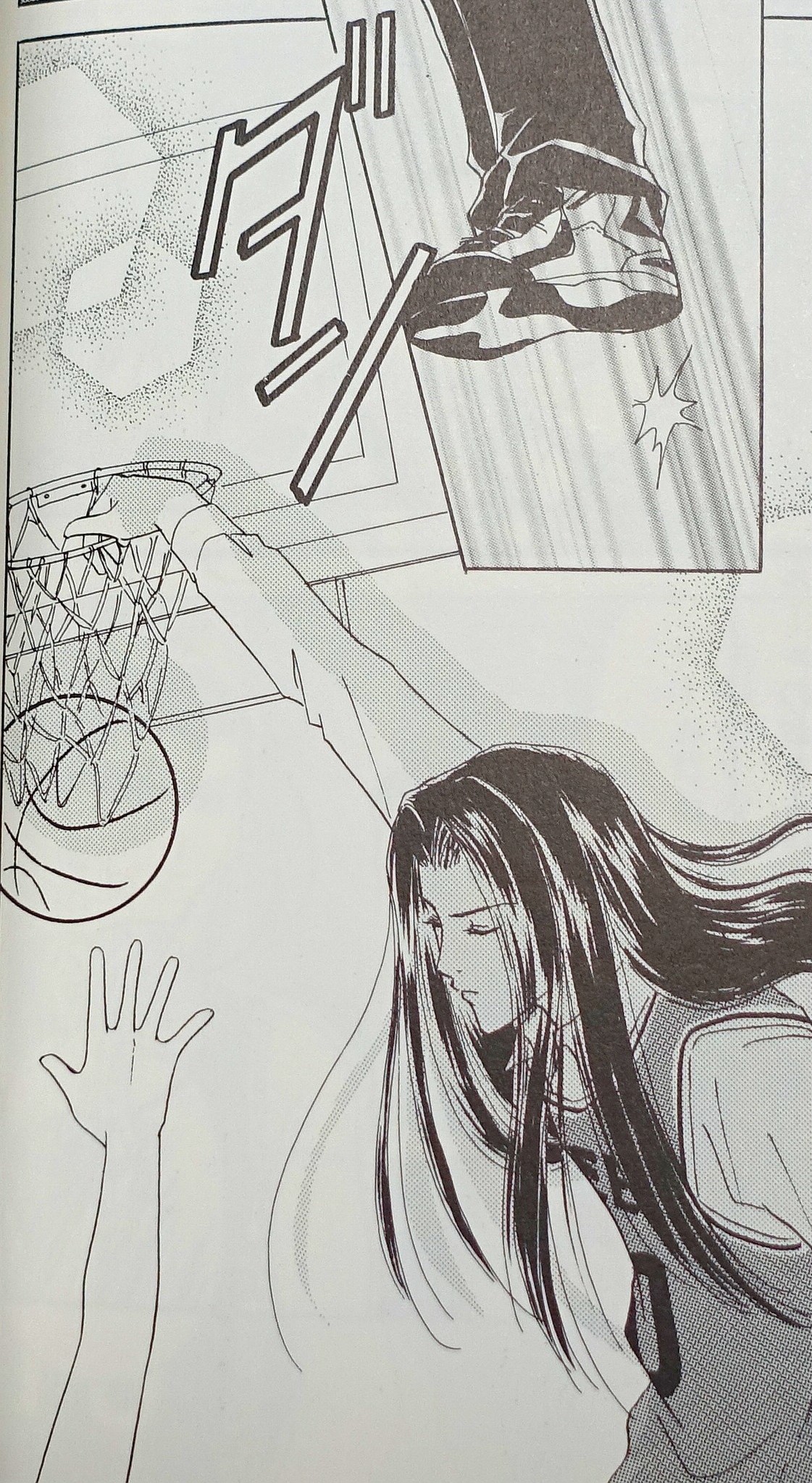

Enclosed please find an assortment of brief, quizzical evaluations of vintage Capcom titles. This was kicked off by the Bard switching from his usual warm-up game of Rastan to Magic Sword. It looked neat; I wanted to give it a try! The quickest legit way that came to mind was the volume of the Capcom Classics Collection I didn't have on the PSP - but the retro price boom has hit that platform as well, and the cheapest copy on Amazon commanded as much as the game did when it was brand-new. It was then that I remembered the Capcom Arcade Stadium collections that were released last year. I checked Steam, and sure enough: Magic Sword and a bunch of other titles were there, available à la carte for $1.99 each! The base launcher was even free!

Sounds great, but I gotta say: save for the non-negligible ability to play these titles in 3840 x 2160 (well, 1920 x 1080 - the launcher will sometimes ignore your specified resolution), I found the PSP Capcom Classics Reloaded a far more enjoyable way to play Capcom retro titles. Arcade Stadium does everything it can to get between you and the games. Dismiss 10,000 tutorial screens! Turn off screen tilting and filters! Hey! Do you want to use the rewind function!? No? Too bad! We've mapped it to the right trigger and made it go off if you so much as breathe on the button! Oh, and the other trigger has a speed up/slow down function that's adjusted who knows how, because the same button controls time in opposite directions, apparently! (I don't have a problem with those who want to use these assists, but they shouldn't be effectively foisted on those who choose not to use them.) Also: we've mapped inserting a coin to depressing the R stick, when no one should use depressing an analog stick for any input ever, much less something as important as continuing!

And I'm not even unlocking cool concept art by playing a slot machine with Street Fighter II sound effects.

So I'm afraid the Arcade Stadium launchers were deleted as soon as my gaming experiences were concluded. As the unexamined title is not worth playing, though - or, well, it is; fun is fun, of course, but it's nice to talk about games, too, and as this is a space for doing so, here are brief thoughts on some random famous arcade titles with which I took this opportunity to catch up.

Magic Sword: I played this last night and have near-completely forgotten the particulars of the experience in the interim. You're a swordsman climbing a 50-floor tower of side-scrolling hack-'n'-slashing and intermittent mild platforming, occasionally facing a boss (one of two, a palette-swap of a dragon or a chimera). The big gimmick is that you can rescue a variety of partners from the tower to fight alongside you - bow-wielding amazons; thieves who spot hidden treasures; skillful lizardmen who want diamond bribes - and you both level up independently; not too far, though.

It looks good, but while there is some visual variety, there's not enough for its 50-level length. The same could be said for gameplay, actually. There are lots of options for partners and power-ups, but I don't feel like exploring them through replays? Your options just don't seem to alter the basic gameplay that much. It simply goes on for too damn long. One of your partner options is a bald wizard. I got some mileage out of pretending that he was Solas. More fun than I was getting from the game in the later stages, actually.

It's fine, in that unenthusiastic, dismissive sense of the word. I'll probably play it again a few years from now when I forget how undistinguished it is. It's better than The King of Dragons (which I rate lower than most - it's a cardboard-cutout gallery of a beat-'em-up) but worse than Knights of the Round as far as Capcom medieval action goes. I greatly prefer Mystara to all three of these. Magic Sword did, however, prove the most successful of this campaign's entertainments, as we shall see.

This screenshot deserved to be in 3840 x 2160, you lying launcher.

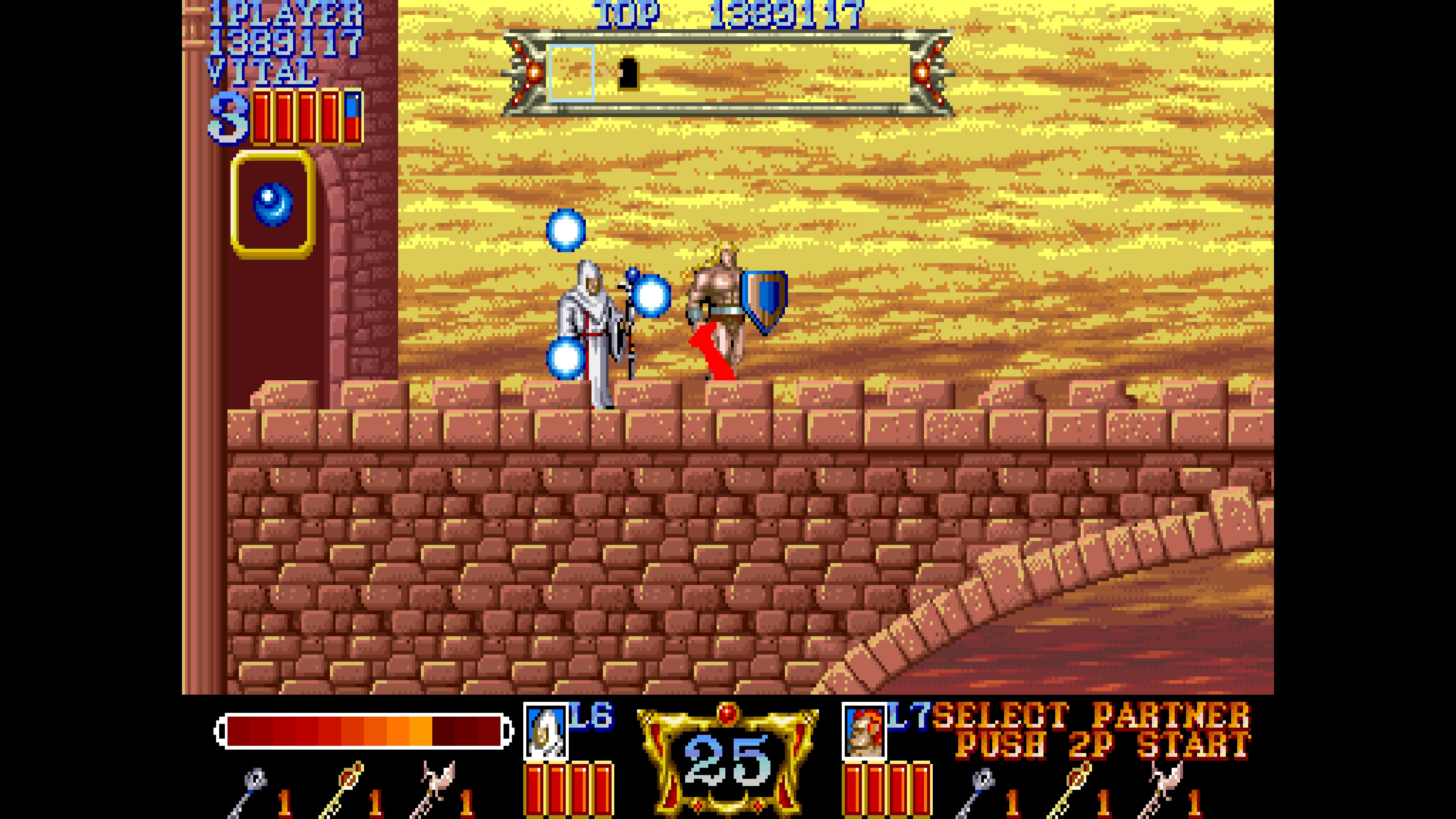

Forgotten Worlds: There are some interesting visuals in this mostly-sidescrolling shoot-'em-up, aesthetics derived from a blend of technologically-advanced alien lizardmen and ancient Egypt (which I'm sure is the foundation for a racist conspiracy theory somewhere). Some impressive stuff, too, like a massive full-screen boss you have to take out muscle by muscle, or the famous interstitials, such as the bold challenge to eukaryotes above. I like the idea of the 360° shooting, yet there seems to be a slight mismatch between your speed and the speed with which the enemies appear? You seem just-so-ever too slow to react, yet I think if you were sped up, you wouldn't have enough control? Maybe I'm just bad.

Anyhow: despite this, I was having an all right time until halfway through the game, when I got completely depowered upon respawn for some reason - I even lost my option, which is base equipment - and got caught in a positive feedback loop where I couldn't defeat enough enemies to afford the current power-ups, falling further and further behind in the arms race to the point where even the most humble mooks were too bullet-spongy for my peashooter. I was dying literally every few seconds. Even the mohawked heroes stopped bothering to show up between levels to comment. I don't know if the depowering that kicked this off was intentional or a bug, but the results were just awful.

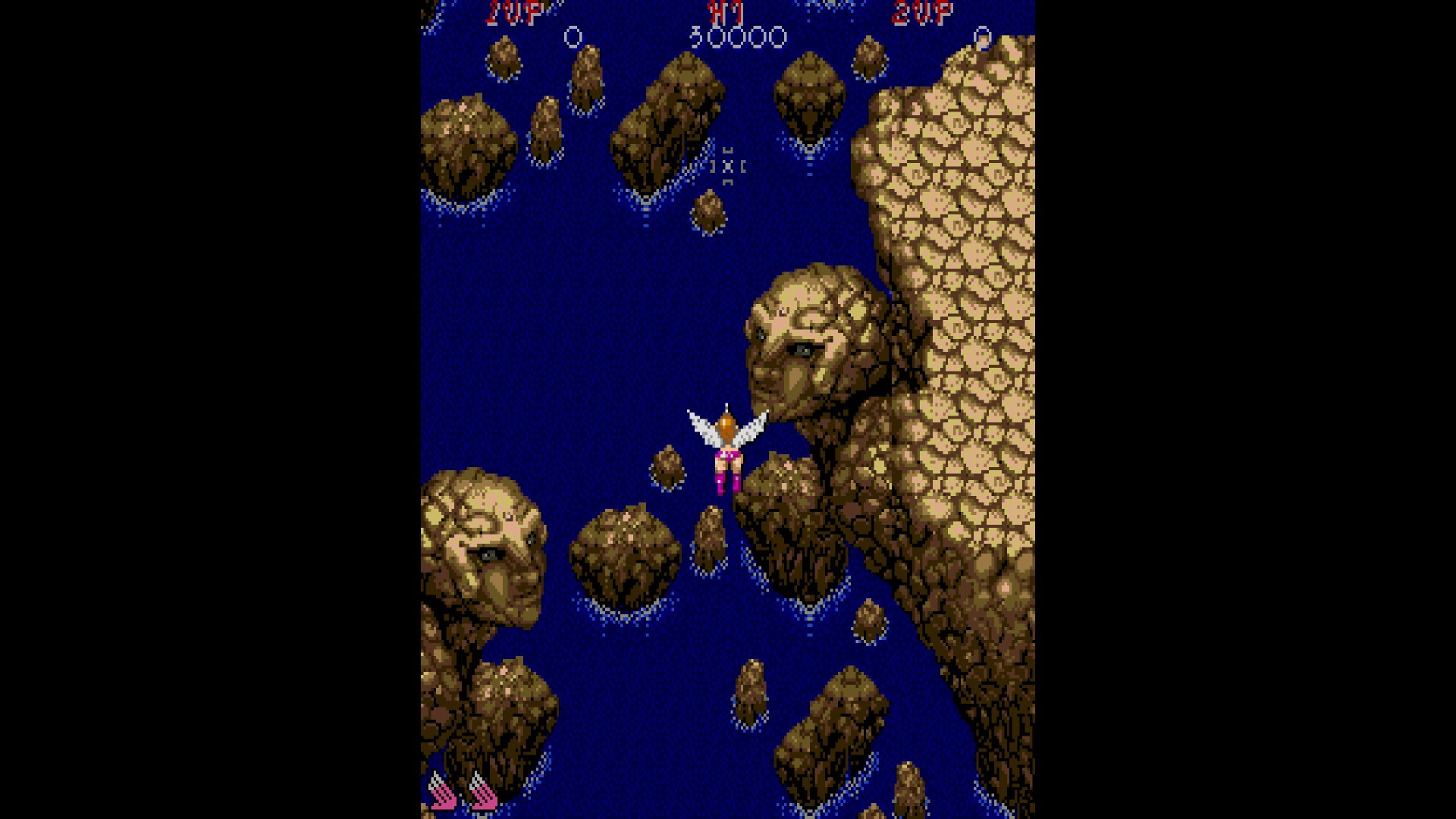

Legendary Wings: I considered this a gap in my gaming knowledge, being a relatively well-known title in its NES incarnation, but it didn't pass the vibe check for this expedition, so to speak. It's one-hit deaths; you can't credit-feed your way through because you restart at the beginning of the stage, not where you died; and your character's jump in the mandatory side-scrolling sections is complete garbage. Perhaps it takes some acclimation, but instant gratification, and not patience or skill, was the theme of this venture. So I moved on to a title totally unknown to me that caught my eye while I was scrolling through the selections:

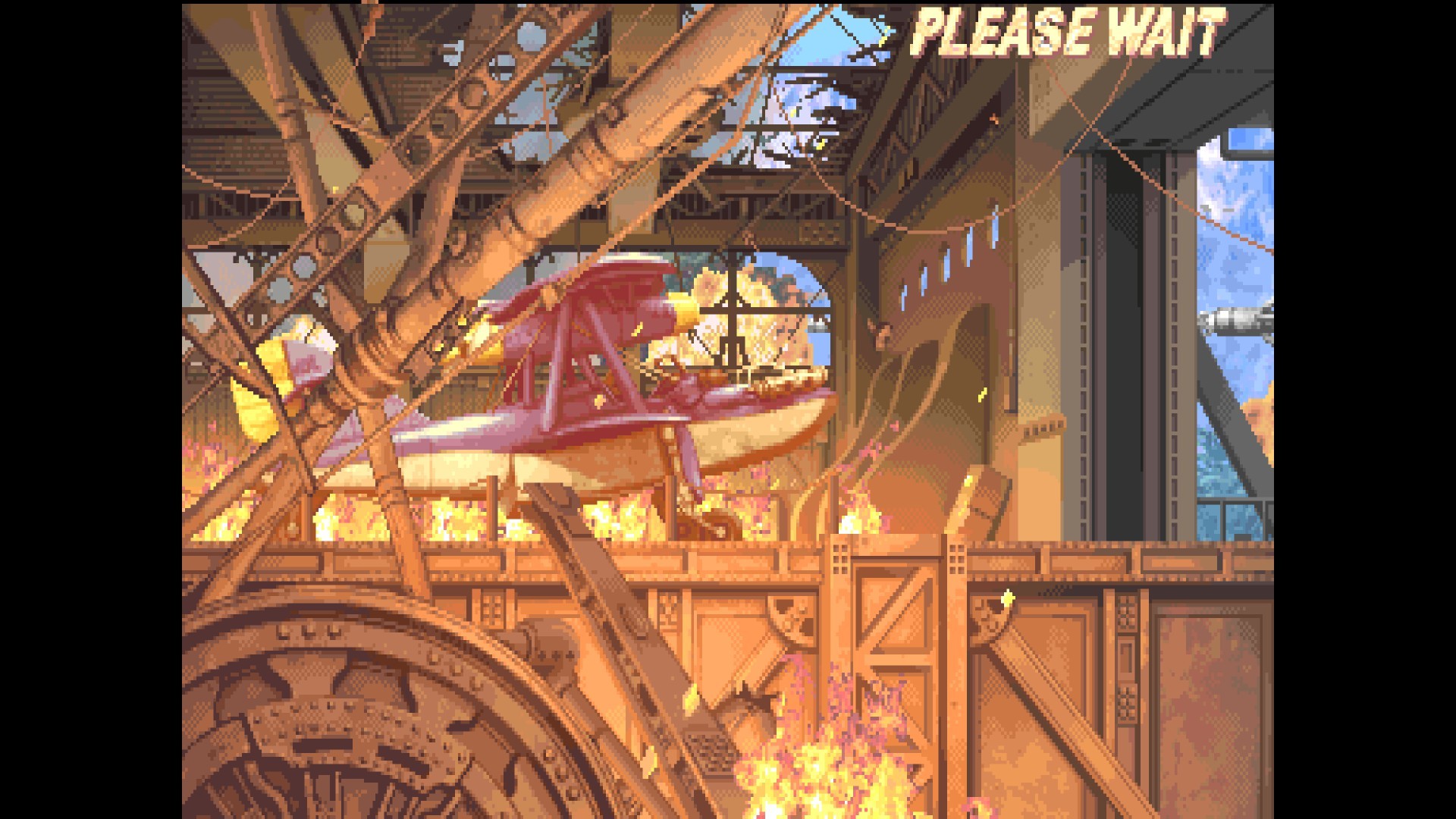

Progear: Forgive me for what is going to be a big "I don't get it" to an entire genre. I was drawn in by Progear's utterly gorgeous pixel renditions of a quasi-European WWI-era landscape. Those utterly gorgeous graphics proved near-completely unappreciable, however, as Progear is a very aggressive bullet-hell shooter. I knew this was a title by Cave, for whom bullet hells were bread-and-butter, but I wasn't prepared for this iteration of the formula to go down so like Marmite to me. Bullets kill you in one hit, but only sometimes? The only reliable tell is if they have you pinned in an inescapable situation, whereupon they are 100% lethal. Your only defense is a limited supply of bombs, which, upon activation, grant you an invincible force field for a bit and turn all bullets into bonus items. Therefore, the best way to play Progear is consume all your bombs, get as far as you can in the fifteen seconds or so they'll buy you, then see how many seconds you can dodge until the bullet-lethality coin toss turns up tails for you and you lose a life, whereupon you use your new stock of bombs to get a little farther - rinse and repeat. It sucks and takes any skill or challenge out of the title, but it's the only way to see anything.

Shmups are, like beat-'em-ups, a "sit back and turn your brain off" genre for me. I just want to enjoy the reflexive action and spectacle. I don't at all enjoy staring at a little bunch of dots and squeezing my avatar through the tiny gaps between them, and I don't see the point to expending anything on graphics when you by necessity have to keep your eyes glued to a very, very narrow slice of the screen and can't look at anything pretty or fun.

In conclusion:

"Love and Courage"? That isn't the Ares I know.

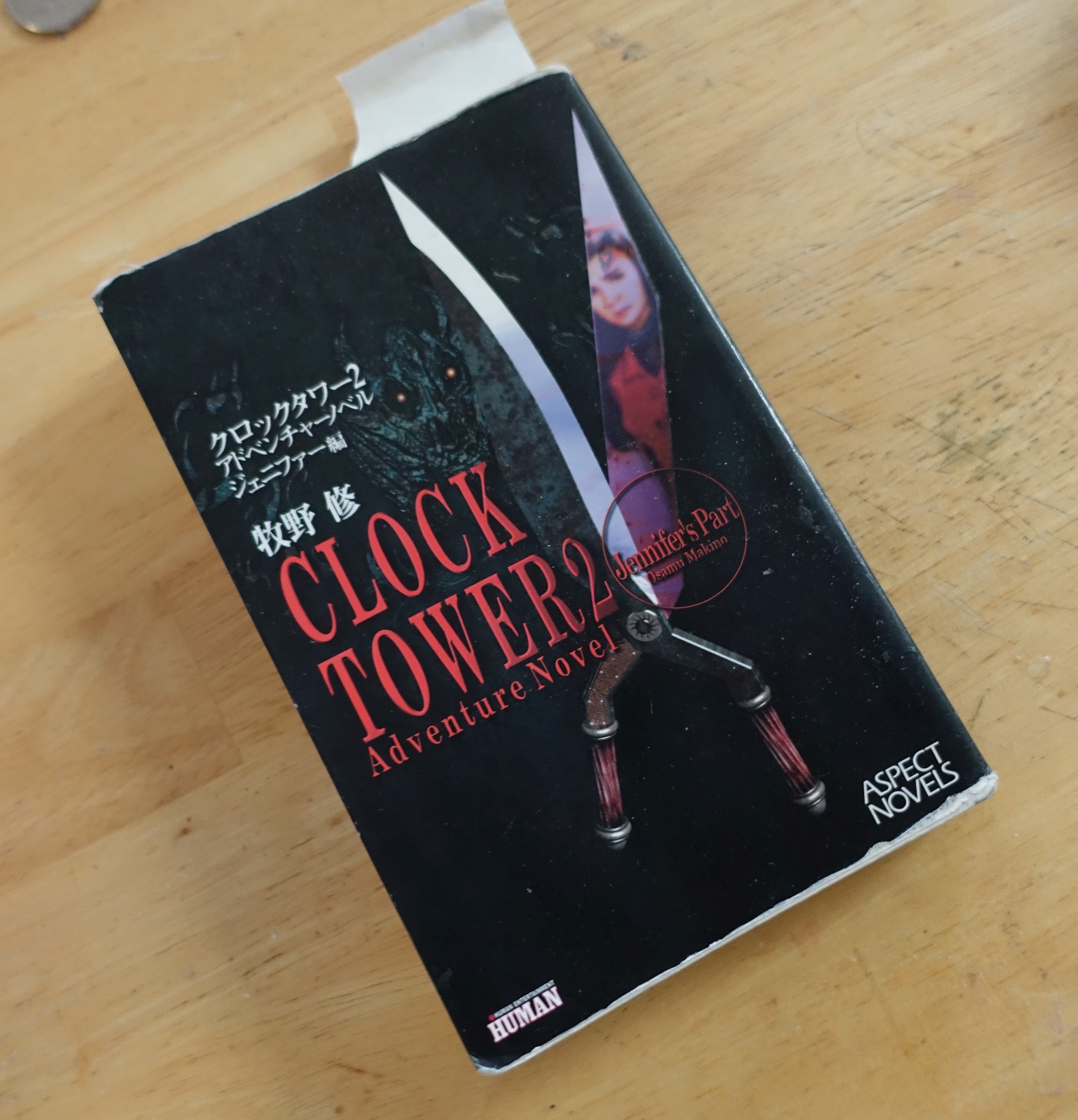

I did it! At long last, I finished translating the Clock Tower Adventure Novel: Jennifer's Part. 303 pages of scissor murder for your perusal - double that if you count the long-released Helen's Part.

And what better way to cap off this experience that with an iconoclastic list-based article! Here's the premise: I don't like the depiction of the final confrontation in the A route of Jennifer's novel as much as in the B/C route. Spoilers ahead!

Page 17 of 56